Understanding sexual health

Sexual health today is widely understood as a state of physical, emotional, mental and social wellbeing in relation to sexuality. It encompasses not only certain aspects of reproductive health such as one’s ability to control fertility through access to contraception, abortion and avoiding sexually transmitted infections (STIs), but also the possibility of experiencing pleasurable and safe sex, free of coercion, discrimination and violence (WHO 2015).

Achieving sexual health

Those who are deprived of – or unable to access – information and services related to sexuality and sexual health, are also vulnerable to sexual ill health. Indeed, the ability of individuals to achieve sexual health and wellbeing depends on their access to comprehensive information about sexuality; knowledge about the risks they face; vulnerability to the adverse consequences of sexual activity; access to good quality sexual health care; and, access to an environment that affirms and promotes sexual health. Discrimination and inequalities are not only detrimental to sexual health but also constitute a violation of human rights (WHO 2015).

Contraception

The continuing increase in the use of contraception since the 1960s has contributed to a reduction in maternal mortality (Feyisetan & Caseterline 2004). It is estimated that one in three deaths related to pregnancy and childbirth could be avoided if all women had access to contraceptive services (United Nations Population Fund 2014).

It is estimated that a doubling of the current global investments in contraceptive and fertility regulation services – so that more women have better access to needed services – would reduce unintended pregnancies by more than two thirds; from 75 million to 22 million. It would also reduce unsafe abortions by almost three quarters; from 20 million to 5.5 million and deaths from unsafe abortion by more than four fifths; from 46 000 to 8000 (Guttmacher 2010).

As both a sexual health and contraceptive nurse and a registered midwife, I ask: ‘What is MAMA providing and what can MAMA do?’

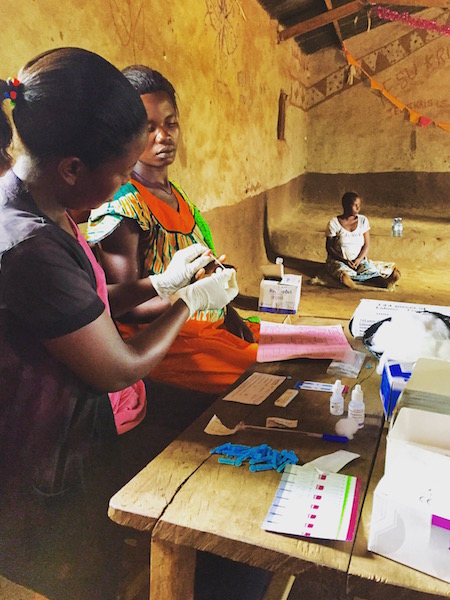

HIV screening

At present, we have HIV screening every 8 weeks, plus a follow up every 4 weeks with treatment at our outreach clinics. Also as of 1st February 2017 we can offer these services 24/7 in our new maternity clinic run by midwives from Azur Clinic. This is a free service to pregnant women and their partners. We also offer screening to non-pregnant persons for a small fee, if they have the means to pay.

What more could we do?

Looking towards a more easily preventable health issues syphilis came to my attention: What about syphilis screening? It could be run alongside the HIV screening and treatment dispensed every 4 weeks to those who need it. Partner notification and treatment could be highlighted at point of test result and asked to attend for treatment subsequently. It is a standard implemented by the World Health Organisation that all pregnant women around the world are screened for Syphilis upon booking.

The Ministry of Health in Uganda recommended Syphilis screening to all. But no funding is dedicated for this so women currently have to pay for their screening and treatment in Hoima District, where MAMA is based. MAMA would like to offer this level of care until a wider screening programme is put in place by the government.

Why Syphilis?

10.6 million new cases of Syphilis were identified worldwide in 2008. One third of these cases was identified in Sub Sahara Africa (WHO 2008); a statistic unchanged since 2005. The Lancet Stillbirth Series reports as many as 1.1 million of these stillbirths could have been averted in this period with Syphilis detection and treatment preventing 136,000 of them; more than twice that of hypertension detection in pregnancy and four times that of malaria detection and treatment in pregnancy (WHO 2009).

Treatment

Access to essential medicines is guaranteed as part of the right to health; they must be available within the context of functioning health systems at all times, in adequate amounts, in the appropriate forms and dosages, with assured quality and at a price the individual and the Community can afford (UNCESCR 2000, Hogerzeil et al 2006, WHO 2003). In spite of this, medicines, sexual health, human rights and the law needed for the promotion of sexual health, such as antiretroviral for HIV, emergency contraception, Mifepristone and Misoprostol for medical abortion – all of which are included on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (WHO 2011) – are often either not available (due to intellectual property laws), or are restricted or prohibited by law.

MAMA has therefore invested in the sustainable availability of testing strips, allowing testing of all pregnant women and treatment of Syphilis, to provide availability of the most effective medicines and assure the correct use of testing and treatment for Syphilis, as set out by the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (WHO 2011).

This provision has been provided from April 2016 onwards to all our women access MAMA’s care.

by Harriet Jacobs RM, CASH Nurse

WHAT MAMA IS DOING

Rapid HIV & Syphilis screening every 8 weeks with treatment at our outreach clinics.

Testing of all pregnant women and treatment for Syphilis

Investing in the sustainable supply of testing strips

HOW YOU CAN HELP

Thank you!

References

Guttmacher Institute. Facts on investing in family planning and maternal and newborn health. New York (NY): Guttmacher Institute; 2010.

Feyisetan B, Caseterline C. Fertility preferences and contraceptive change in developing countries. New York (NY): Population Council; 2004.

Reducing risks by offering contraceptive services. New York (NY): United Nations Population Fund; 2011 (http://www.unfpa.org/public/cache/offonce/home/mothers/pid/4382, accessed 1 May 2014).

General Comment No. 14: The right to the highest attainable standard of health (Article 12 of the Covenant). New York (NY): United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; 2000 E/C.12/2000/4).

Hogerzeil HV, Samson M, Casanovas JV, Rahmani- Ocora L. Is access to essential medicines as part of the fulfilment of the right to health enforceable through the courts? Lancet. 2006;368:305–11.

The selection and use of essential medicines. Technical Report Series, 920:54. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. 17th list. Geneva: World Health